What do you think the most important element of a film is? Is it the frame, is it the theme or the narrative or the lighting or the sound? Well, that’s a debate that could be done with intellectuals bashing their heads on the table while not finding a correct answer. While the answer is Stanley Kubrick. Why is it so? Because he was the one who made us believe that even if it is not a great story, it could mess up your mind if you have the correct vision. He was not only the Master of Visual Art, cinematography, music or just one thing, for me he was the auteur in a true sense. While like his films, it is very critical to write about him because you could write everything, yet something will be left behind.

STANLEY KUBRICK was born to a Jewish family in the Bronx, New York. His father Jacob Leonard Kubrick was a physician. But he introduced his son Stanley Kubrick to Chess and Photography, which became his lifelong passion that would deeply influence his filmmaking. Kubrick, as a student, struggled in academics, especially in a traditional school setting, which we could see a reflection of in his films like Clockwork Orange. But he was an average student. After his high school, he pursued one of the passions that was introduced by his father as his career, i.e., photography. And at a very early age of 17, he became a staff photographer at Look magazine. He worked there for 5 years, from 1945–1950. And in these years involving himself with photography, he developed a strong eye for composition and storytelling.

Fear and Desire: The $10,000 Film Kubrick Disowned

Kubrick, after getting out of Look magazine, began making short documentaries in the early 1950s, such as The Day of the Fight (1951) and The Seafarers (1953). His first feature film was Fear and Desire (1953), which was a low-budget film (around $10,000) produced by himself, which was a war allegory. He was so detached from the film and dissatisfied that he later disowned it, calling it a “bumbling amateur film exercise.” He even actively prevented it from being shown publicly and tried to suppress prints and screenings. But later, Kubrick’s long-time assistant Leon Vitali discovered a 35 mm print of the film in Kubrick’s private collection. In an interview and documentary (Filmworker, 2017), Vitali states:

“Stanley did not want people to see Fear and Desire. He was really embarrassed by it…. He just said, ‘Don’t show it. Don’t talk about it.’”

Matter of fact, Vitali himself never had watched the film, because Stanley Kubrick hated it so much.

Despite the disapproval from Kubrick, Fear and Desire was eventually restored and released in the 2010s by institutions like the Library of Congress. It is now viewed more as a historical curiosity rather than a valuable part of Kubrick’s filmography.

Kubrick Beyond Genre: How Voyeurism, Framing, and Control Define His Cinematic Language

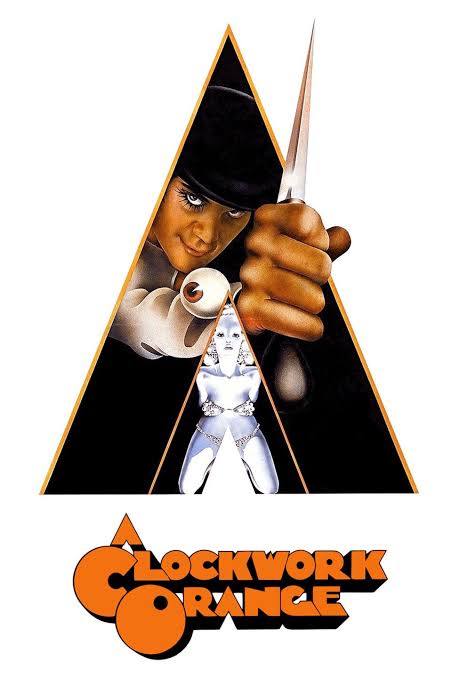

Stanley Kubrick has been erroneously interpreted nowadays. It’s better to state that interpretation of a specific film is our personal way of viewing, but demarcating a particular filmmaker into a specific genre or theme disrespects his entire body of work, especially Stanley Kubrick, where every film is different from each other. I have seen circles talking about Kubrick as someone who is a horror film director or a sci-fi film director, despite doing films like Dr. Strangelove, Barry Lyndon, Eyes Wide Shut, and most importantly Clockwork Orange. Clockwork Orange is a film that is very difficult to categorise as a genre, especially not in sci-fi or psychological thriller; the story provides a very surreal understanding of reality, choice, and the symbiotic relation of good and evil. But even though we sometimes don’t understand the film, we get trapped in his films. But why? Why do we feel trapped in the film even though it is strange to us?

Kubrick’s biggest theme in his films is making the viewer part of the story. Even though the narrative might not seem familiar to you, it eventually traps you in the narrative by repetitively making you the subject within the films. But how does he do that?

If we watch his films closely, we will find that he moves his camera in such a way that it feels like someone is watching voyeuristically. And this voyeurism is pretty evident in many of his films. In Shining, we could see that someone is watching them throughout the film while they are in the hotel. Whether when Jack is sitting in the hall of the Overlook Hotel typing on his typewriter or when someone is going through the staircase. Especially in the scene when Danny is riding the bicycle through the hallway, the camera moves in a way that it feels like someone is chasing Danny. These point-of-view shots are evident throughout the film. Or in the film Path of Glory, the scene where the officer is going through the tunnel and the famous tracking shot could be found. Here the camera moves and frequent POV shots could be traced.

Similarly, he uses framing and composition too as an extension of his perfectionist mentality. In the film Full Metal Jacket – Boot Camp Drill scene, where Sergeant Hartman enters from the right third of the frame, walking along soldier rows. He is always placed off-centre to maintain visual imbalance. It also shows the power dynamics. Kubrick uses the steady framing to enforce relentless discipline; recruits pass through thirds in perfect synchrony. But Kubrick still takes one step further by framing the shots to visually show the idea. He frames it in symmetry and cadets standing in an organised manner forming a leading line. And eventually, the second half of the film loses this uniform sense and rigidity, stating the world’s state of losing it. The framing works according to the narrative.

Stanley Kubrick was a Perfectionist.

Watching Kubrick’s films feels so dreamlike or perfect that we can’t stop thinking about them. But how were his films so perfect, and why does the acting in his films feel so real?

Kubrick’s perfectionism, though visionary, frequently came at the cost of his actors’ well-being. There are tons of examples. Shelley Duvall, who played the female lead in The Shining, states her exhaustion while playing the role and how Kubrick pushed her to her limits in pursuit of authenticity. Remember the iconic staircase bat swing scene? Kubrick made Duvall film the iconic scene for 172 takes, leading to exhaustion, dehydration, hair loss, and physical strain. She described the shoot as ‘hell to be part of’, even though she acknowledges and praises Kubrick’s tendency to find the perfect reaction or scene.

Similarly, in Clockwork Orange, Malcolm McDowell suffered temporary blindness because of him. During the Ludovico technique scene, his eyelids were forced open with the clamps used in medical eye surgeries. The scene is too long in duration and so eye-shattering, it’s quite literally painful to watch (pun fully intended). Because of the use of the clamps for a long duration, they scratched his cornea and caused temporary blindness. But even though he was feeling irritation in his eyes, Kubrick asked to keep the scene going in the close-ups because “his eyes are the character.” In Eyes Wide Shut, a door walk scene was shot 95 times, inducing stress and an ulcer. Because of his control-freak nature, he had his clashes with many actors starring in his films, like veteran Adolphe Menjou, Kirk Douglas in Spartacus, and actor Matthew Modine in Full Metal Jacket.

Even in his film narrative and filmmaking, he was a control freak, not thinking of any rules or techniques, leading to inventing his own set of techniques. Christopher Nolan, in an interview, states, “What Kubrick did in 1968 is he simply refused to acknowledge that there were any rules that he had to play by in terms of narrative.”

Where Classical Hollywood cinema focuses on how to engage audiences while not keeping unnecessary long cuts and takes, he did the opposite. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, he kept a long introductory scene of apes fighting and roaming a deserted land which is around 20 minutes long. While it seems illogical to many, it was needed to show the evolution and the eventual changing of time and pace of the fast-evolving generation. Obviously, the film shows his visionary ideas about technology. The film also has fewer dialogues, especially in the opening and final scenes. The protagonist keeps shifting: prehistoric apes ➝ HAL 9000 ➝ Dave Bowman ➝ a star child. Even though The Shining is a horror film, it is devoid of unnecessary jump scares and constant supernatural happenings. The slow turning of Jack into an oddly behaving toxic works as gradual development.

He broke the grammar of filmmaking while making new ones and became an inspiration and avid example for many, like Christopher Nolan, Steven Spielberg, and more.

Ranking his best work and Clockwork Orange

I have seen so many articles on the ranking of Stanley Kubrick’s filmography. So, putting one more would not make any difference (like rotten tomatoes or studiobinder article on the ranking). Instead, let’s talk about which are his best movies according to me and why. Even if I rank, the most predominant level in the rank will be Clockwork Orange in the first place.

Clockwork Orange blew my mind, in every sense. Whether it is visuals, photography, narrative, or the use of colours. Let’s agree on a part that the story of Clockwork Orange might not be as fascinating to many as someone would find in Alfred Hitchcock’s psychological thrillers. But that’s the best part, even though the story is not such a masterpiece, Kubrick made it something extraordinary. He uses the full power of the film medium to tell the story.

It was adapted from Anthony Burgess’s novel; the film represents a dystopian world through the lens of Alex. Alex, a charismatic yet psychopathic protagonist, commits acts of ultraviolence with disturbing nonchalance. The film shows how good and evil have a symbiotic relationship. The constant contrasting colours throughout the film work in favour of that. Everyone in the film wears oddly contrasting colours, whether it is red or green. But the goons always wore white costumes in contrast to everyone. Alex, though very psychopathic, still has deep emotion and understands music. One of the most striking and horrifying scenes for me was when Alex and his mates went to an old writer’s home to assault them. During that scene, when he was assaulting the writer’s wife, he was singing ‘Singing in the Rain’ one of the most soothing and romantic songs ever. The song works as a striking contrast to the scene. And when, again, after coming from prison, Alex went to the same home and the author did not realise it was him. He started singing the same song in the bathroom, and the old man was seen getting mad and exhausted by the rhythm.

The theme keeps raising the question even turning someone into ‘good’ without their own consent is that viable and legitimate? And let me not disclose this to you for someone who is reading this and hasn’t watched the film yet. When you watch the ending scene of Alex dreaming of a series of sequences, it will raise the question of conscience again.

Because of the graphic depictions of violence and moral ambiguity, Clockwork Orange was arguably one of Kubrick’s most controversial films. The combination of stylised violence, classical music, and dark satire led to widespread moral panic, especially in the United Kingdom. Even though BBFC (British Board of Film Classification) passed it with an X-rating, due to public outrage and media scrutiny, Kubrick decided to withdraw the film from UK cinemas in 1973. It remained unavailable in Britain until 2000, when it was re-released one year after his death.

Conclusion

Stanley Kubrick is a very complex director, and watching his film once might not work for someone, especially like me. But when you return to the films eventually for the second or third time, you will start realising your own conscience and question your sense of evil and bad. But his imagery and use of light and colours might seem peculiar and strange to many like he uses green specifically in his films to symbolise death or uses it to stage it. And it will astonish many how a colour like green could symbolise death, but it does because Kubrick does that, and he feels that. He is one of the most controversial filmmakers ever in the history of films because he raises questions about something that you have never ever imagined. Maybe that is why he eventually became so relevant and one of the cult classics. There is a reason he is a master of this process of filmmaking, and watching his film will make you believe that.